A Season of Unrest

(Adapted from John Leitch, MAN-TO-MAN: THE STORY OF INDUSTRIAL DEMOCRACY (New York: B. C. Forbes Company, 1919), Chapter III, 30-62, except as noted.)

Albert S. Bond attended a meeting of the Quest Club on January 29, 1913, that had been announced in the morning newspaper.52 What John Leitch proposed to about 60 business executives in the meeting appealed to Bond as a possible solution to the problems he was facing in The Packard Company.

In 1911, a “walking delegate” appeared in Fort Wayne to unionize the town. Within a few weeks, Mr. Bond was approached and asked for permission to have the union recognized. This he readily agreed to.

After the union became sufficiently strong, the leaders approached President Bond and demanded that the Packard company become a “closed shop.”

“What am I to do with workers who don’t join the union?” asked Bond.

“Then I guess we’ll have to treat them as scabs,” remarked the agent carelessly… “you know we union men can’t work with scabs.”

With the union threatening to strike, President Bond acted quickly, shutting down the factory on April 27. In an interview with the Journal-Gazette reported 2 days later, he explained the closing:

…only two-thirds of the 250 or 300 employees of the factory are affected by the temporary shut-down…while one-third will be retained in the various departments. No distinction has been made between union and non-union men in picking the men to be retained…the temporary closing of factory departments was determined some time ago in order to conclude several important changes in the works, entailing the shifting of several departments and the installing of new machinery…

Asked whether or not all of the present workmen would be given employment again at the completion of these changes, Mr. Bond stated that this would very likely not be the case owing to the present condition of the piano market. “It makes absolutely no difference to us,” concluded Mr. Bond, “whether our employees are members of a union or not. That is their own business. We have always conducted our factory as a so-called ‘open shop’ and we will continue to do so.”

On May 12, the paper reported that the “Operations at the Packard Piano and Organ factory will be resumed sometime this week, and the men out of employment…will then be recalled.” With President Bond having stood his ground, the Packard company would remain an “open shop.”

While the threat of a strike had ended and production had resumed at the plant, there was a lingering attitude of dissatisfaction and unrest. The output was negatively affected, as well as the quality, and the company began to receive complaints from their dealers about defective instruments. Even though Mr. Bond had attempted in all situations to be fair to his employees,

paying them a fair wage for a fair day’s work, he was at a loss to know where to turn or what to do. There was no clear communication between management and workers.

After hearing Mr. Leitch at the Quest Club, Bond determined to contact him and see if he would be willing to come to Fort Wayne. After persisting for some nine months, Mr. Leitch was convinced President Bond was serious: “I feel that I am somehow to blame here; I cannot get down to the men; they do not trust me although I am as fair as I know how to be. I simply have not sold myself to them. I shall do anything you tell me to do. I put myself in your hands.” John Leitch agreed to take on the challenge of bringing workers and management together to come up with an agreeable solution.

John wasted no time after arriving at the plant. After he spent a few days getting familiar with workers, management, and the plant, a general meeting was called for all involved. It was held intentionally on company time. All were told that it was time to be open and honest with each other; the decision was up to them if they wanted to work together towards a common goal as up to this time workers and management had been working at cross purposes. All shared blame for the situation equally. While many were skeptical, they still listened. It sounded intriguing enough that they agreed to give it a shot.

Weekly meetings were held and the groundwork was laid for developing a common policy. Mr. Leitch talked about justice and offered as the first cornerstone of the policy the following resolution:

We, the Employees, Officers, and Directors, recognizing that Justice is the greatest good and Injustice the greatest evil, do hereby lay and subscribe to, as the first corner-stone of our policy, this greatest of all good.

JUSTICE

The fullest meaning of this word shall be the basis of all our business and personal dealings – among ourselves as individuals, between our company and those of whom we buy, and between our company and all those to whom we sell…

After much discussion and assurances that the resolution was not just a lot of words, it was adopted unanimously. They adjourned for a week.

Each weekly meeting saw a new cornerstone being agreed upon. Following Justice came Co-operation, Economy, and Energy. This structure was followed with a Capstone of Service.

Once the policy was finished and adopted unanimously, all signed the document. Each person received a personal copy, and the policy was visibly posted throughout the plant.

A change was noticed; it was a different crowd of men who came to work. The weekly meetings continued as all took ownership of running the factory and helping to make improvements.

Quality improved, production increased, and company earnings were up. President Bond, along with the other managers and directors, agreeing that the company should not be the only one to benefit, agreed with the workers to a 50-50 split of the increased profits.

Working together, the men were able to help remedy problems that arose. The result was that at the end of the first month the force had cut production costs five and half percent which was divided equally between them and the company. For several months they kept on averaging 5% or more, as they put their whole selves into the work.

The work week had been 60 hours, but the workers negotiated down, eventually agreeing to an eight-hour day, 5 ½ days per week. Efficiency and output were greatly increased which resulted in more profits.

Other benefits were noticed beyond the factory. Mr. Bond wrote, “We have had several instances where the wife of a Packard workman came to us and asked ‘What are you doing to your men?’ When we asked her why she wanted to know she replied, ‘Well, something has happened for my husband is better to me and the children.’”

By the end of 1914, a new slogan had been developed: If there is no harmony in the factory, there will be none in the piano. It quickly found its way into all their advertising.

After several years of working under the policy, the men themselves formally stated that “…a democratic administration, guided by fair business policy, has accomplished these ten things: 1. Reduced working hours, 2. Increased the output, 3. Produced better instruments, 4. Increased workmen’s income, 5. Put the whole man to work, 6. Done away with misunderstanding, 7. Given each man a share of the responsibility, 8. Made real inventors of many workers, 9. Instilled a spirit of genuine comradeship into the entire organization, and 10. Established a new kind of democracy.”

As John Leitch noted, “But what of union trouble, what of the closed shop? What happened to the original grievances? They got lost in the shuffle.”

As a consequence of the adopted democratic business policy, the company weathered the storm of the outbreak of World War I in August of 1914. Piano sales had come to a screeching halt, and Mr. Bond was in a quandary as to how to help the factory weather the crisis. However, it was the men who approached him with a solution. They offered to work a three-day week in order to cut production costs. The president was astonished.

Realizing the severity on the income of the workers, Mr. Bond pushed back. A four-day work week was settled upon after he was able to produce facts that convinced the workers it was a financially viable option for the company. In addition, the foremen had agreed to a 25% reduction in their own wages for the time being.

The factory continued under this limited schedule until 1916 when business began to pick up. Out of the original workforce, 168 men had remained. One hundred had been unable to meet expenses and had sought employment elsewhere but had left without disrupting the organization.

When President Bond offered to begin hiring back employees as business picked up, the men argued that they could handle the work more efficiently, and that production would not suffer but increase. As again noted by Leitch, “At the time of writing this account [1918], the factory is doing a larger business that any time in its history and the work is being done by 168 men.”

After the success of the Packard Business Policy became known, the company received a “…downpour of letters from all parts of the nation making inquiry.” In order to meet the need, Albert Bond wrote a small 63 page book titled, JUSTICE: THE SECRET OF GOOD BUSINESS in 1920 (Fig. 17).

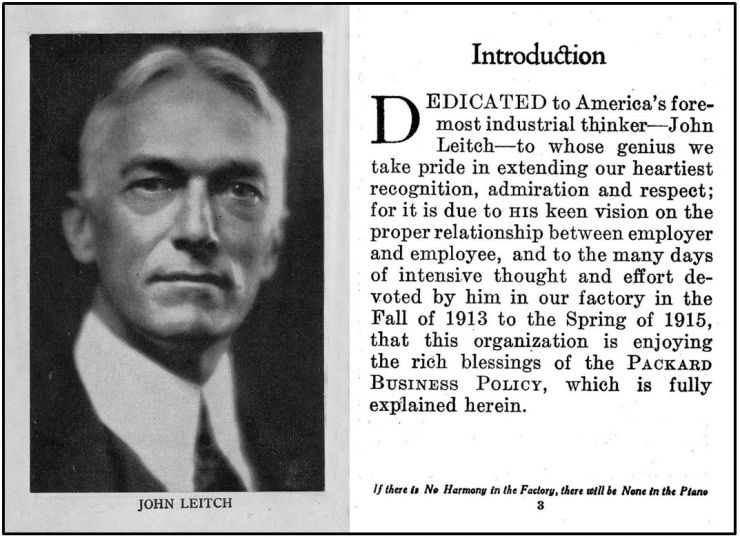

Its purpose was not for advertising but simply to set forth the facts as proven by Packard’s own experiences in the hope that they would be of benefit to other companies interested in Industrial Democracy. He dedicated the book to Mr. Leitch in the introduction (Fig. 18).

Fig. 17. Book: Justice - The Secret of Good Business.

Fig. 18. Dedication to John Leitch.